By ELLEN BARRY

Published: May 31, 2011

BAKU, Azerbaijan — In a mostly empty Soviet-era building here on a recent morning, a 29-year-old woman pressed her eye against the scope of a sniper rifle, brown hair spilling over her shoulder, and took aim at virtual commandos darting between virtual trees

Gathered around her were fellow students — a decommissioned soldier, teenage boys with whispery mustaches, a 34-year-old communications worker in Islamic hijab. When sniper training was offered here in April, by an organization that provides courses on military preparation, the classes were a sensation, attracting three times as many students as the instructors could handle.

The logic behind this can be traced to a grievance that festers below the surface of everyday life, permeating virtually every conversation about this country’s future.

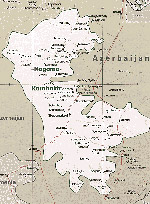

Since the early 1990s, Azerbaijan has been trying to regain control of Nagorno-Karabakh, a predominantly ethnic Armenian enclave within its borders, and secure the return of ethnic Azeris who were forced from their homes by war. A cease-fire has held since 1994, and officials remain engaged in internationally mediated negotiations with Armenia, a process that will receive a burst of attention this month when the two sides meet in Kazan, Russia.

But the window for a breakthrough is narrow, and people here say their patience is gone.

“I’d rather go to war than wait another 20 years,” said Shafag Ismailova, 34, a student in the sniper course, who fled the Zangelan region outside Nagorno-Karabakh, one of seven adjacent territories that are under Armenian control. Asked about war, her friend Shafag Amrahova, a recent law school graduate, did not hesitate.

“War is bad for everyone,” she said evenly. “But sometimes the situation demands it.”

It is tempting to forget about the “frozen conflicts.” The enclaves of Nagorno-Karabakh, Transdniester in Moldova, and Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia are among the most headache-inducing legacies of the Soviet Union. The Soviets granted them a sort of semi-statehood, a status that ceased to exist just as nationalism flared in the ideological void. But the 2008 war in Georgia serves as a reminder of how quickly and terribly they can come unfrozen.

One of the reasons Nagorno-Karabakh has not is that neither party has an incentive to fight. Armenia controls the territories, so it is interested in maintaining the status quo. Azerbaijan sees little way forward: though it could easily drive out Armenian forces, Russia could send its army to help Armenia, its ally in a regional defense alliance, just as it did in South Ossetia.

But conditions have been shifting, slowly but surely, in a dangerous direction. Negotiations mediated by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe faltered last year, leaving a “basic principles agreement” that was five years in the making unsigned by either side. Both countries are engaged in a steep military buildup; Azerbaijan, by far the richer of the two, has increased defense spending twentyfold since 2003, according to the International Crisis Group.

With frustration building, threats of war have become so entwined with negotiations that it is difficult to say where one begins and the other ends.

“There is no guarantee that tomorrow or the day after tomorrow a war between Azerbaijan and Armenia won’t start,” Ali M. Hasanov, a senior presidential aide here, said in an interview. “It’s peaceful coexistence that we need, not a war. We need peaceful development. But nothing will replace territorial integrity and the sovereignty of Azerbaijan. If necessary we are ready to give our lives for territorial integrity.”

He said Baku had been bitterly disappointed by international mediation efforts. “The United States, France and Russia do not do what they promised,” he said. “America now thinks Afghanistan and Iraq are more important — and North Africa, and the missile defense shield in Europe — than such regional conflicts as Nagorno-Karabakh.”

Among the forces driving Baku are refugees who have spent nearly two decades in limbo. The United Nations says there are 586,013 — 7 percent of Azerbaijan’s population, which is one of the highest per capita displacement rates in the world, according to the International Displacement Monitoring Centre.

Though conditions vary widely and some resettlement is now taking place, a visit to a dormitory in Baku found children growing up in squalor. Roughly 100 refugees were living along a dank, fetid hallway, on one floor of a former office building. Three rough, foul-smelling holes in the concrete floor served as toilets for 21 families, residents said. The hallway was open to the elements, exposing residents to bitter cold in the winter. In the summer, mosquitoes breed in stagnant water in the building’s basement, rising in a cloud to the floors above them, they said.

“They cannot stand it anymore, they want war,” said Jamila, 41, of her neighbors. “They don’t believe the promises anymore.”

Just then, a man took her aside, rebuking her for speaking to Western journalists who could, he warned, be pro-Armenian. “Our children look at other houses, they see that other people live well, and they are ashamed,” she said when she returned, refusing to give her last name. “Write that the cursed Armenians are guilty of this.”

In this charged atmosphere, Nagorno-Karabakh has become “the one issue on which there is total social consensus,” said Tabib Huseynov, a political analyst based in Baku. A visitor here a few years ago would have heard “Karabakh or Death,” a rap anthem that accuses the United States, Russia, Turkey and Iran of turning a blind eye, exhorting the world to “either put an end to this, or stand aside.”

Cease-fire violations — every year, snipers kill roughly 30 people on either side of the so-called line of contact — can take on huge proportions. In March, Azerbaijan announced that an Armenian sniper had killed a 9-year-old Azeri boy, Fariz Badalov. Though Armenia’s president denied that his forces were responsible, Azeri television featured the boy’s pitiful life story. One broadcast noted that the single bullet that crossed the line of contact that day was the one that lodged in the boy’s head.

The story inspired Valid Gardashly, a publicist for the Voluntary Military Patriotic Sports-Technical Association, which offers military training from a headquarters in Baku that is reminiscent of a V.F.W. post. The organization sketched out a plan for a 45-day course that would include sniper training, free of charge for about half the students.

“We thought we had to do something,” he said. “We are not preparing for war. But this was a poor boy — what did he do wrong? He was not a soldier. He was just watching cows.”

The course touched a nerve — both in Armenia, where some expressed outrage at the idea, and in Azerbaijan, where an overflow crowd was winnowed down to the 32 most promising marksmen. One who made the cut, a 15-year-old boy, offered his own reason for taking the class: “I am getting ready to fight in Karabakh.” Ms. Ismailova, one of the students, looked anxious as she listened to him. She, too, grew up among Karabakh refugees. But the younger ones are much more ardent, she said.

“These young guys, they have been waiting their whole lives,” she said. “We had a genocide, and no one helps us. Not America, not Russia.”