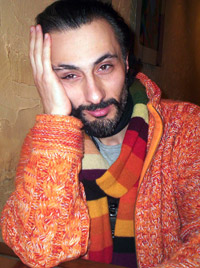

Young film director Arak Sevada (Grigoryan) currently lives in the U.S. He has recently made a film, which although may seem a bit strange for the Armenian audience, however, is pretty symbolic for the Armenian film industry. It takes small investments and not one donation to make a short-budget, short-story film. It all depends on whether the film director wants to produce the film and what kind of ideas he has. Fortunately, we are living in an era where digital technology helps make film production much easier. Artak Sevada is against moaning and groaning just because there are no sponsors. He knows what he is doing and the value of his film. Although he hasn’t learned cinematography in America, however, he has learned how to work hard. While in Armenia, he has noticed that Armenian youth usually likes to start the day off in the afternoon and doesn’t pay attention to what’s happening in the world. There are so many interesting things in life which could be a topic for Armenian artists out there.

Artak Sevada considers his first short-story film “Mikosh” as abstract. The protagonist is a shoe which, according to Sevada, is looking for his soul mate “just like any human being”. The shoe doesn’t fit in the world without its soul mate. “The old yet very modern shoe is much like modern day Armenia. You won’t change the shoe that fits with a new one. You must get used to the new one, but you still want to wear the old one and don’t even dare throw it away,” says the producer of “Mikosh”. That shoe finally finds its owner-a homeless person with one foot. The foot and the shoe find each other.

‘This is a very sentimental topic, kind of like something Charlie Chaplin would star in. It’s about the material world and human relations,” says Artak who sent his short, thirteen minute film to the international film festival in Tirana and won a grand prize in the “Audience Approval” category. “Mikosh” has been shown in festivals around the world. Nobody knows about the film in Armenia and that is why Artak is planning on showing the film during this year’s “Golden Apricot” film festival. This symbolic and sentimental story has also given the film director a chance to produce other films. He has started filming two other films with the 25,000 dollar grant from Albania. The films have been taped in Armenia and he places great importance on that. Artak will soon return to the U.S. to edit the films.

– “Who were the actors in “Mikosh”?

– There were no professional actors in my first film. What I needed were real people. I decided that I just didn’t need actors who just act.

– Who are the protagonists of the two new films?

– One of them is a short film called “Rope” and it’s basically about a rope. The other one is longer and I will either call it “Like the beginning” or “Like the end”. I think that the two have the same meaning more or less.

– The rope will probably find someone’s collar to wrap around, just like the shoe found the foot in the film “Mikosh”…

– If we look at it from that perspective, then it would seem kind of ridiculous, but I am still working on it. Micheal Poghosyan is one of the main stars.

– Don’t you think that Armenians need to watch films that are simple, sentimental and have moral ethics?

– A film has to be real. It has to be about real people. You don’t have to express yourself entirely. That is my opinion. I am mainly interested in people, their daily lives, the village life. One of the scenes in “Like the beginning” takes us back to an Armenian village in 1936 and shows us the poverty and hunger. I like the ordinary villager more than the villager that pretends to be high-class. The second film is going to be more of pantomime and it is also going to have something to do with the village. Sergey Danielyan will play the roles of both director and the villager. The plot will enfold on stage and in reality. I am going to draw parallels in the film, for example, how the present day intelligent person looks at the villager back then and vice versa.

– Have you worked for any large film studios in America?

– I have worked as a production assistant for Warner Brothers for a year and a half. It’s not hard to get accepted to work in major Hollywood studios, but it’s hard to work there. It has to do with my nationality. Americans don’t accept many traits that we Armenians have and they discriminate. If the studio needs ten directors and there is one Armenian and one black among them, then the studio will choose the other eight white Americans. The studio is the one that prepares the plot and it will choose the director which best fits in with American standards.

– But you can’t judge a cover by its book.

- Americans don’t care about that. Film production depends on large investments and the investors don’t like to lose money. I decided not to work with large studios because I like working on my own projects more.

– Do you agree with the fact that a talented Armenian artist must leave Armenia to reach fame?

– Yes, I do. I ask myself: if I were to stay here, what would I do? How would I be able to progress? The right thing is to leave for a while, but return.

– What can the young Armenian directors do if they can’t leave the country?

– They can work. I heard an interesting thing recently. They told me that they wanted to produce a film but they couldn’t. I remembered Atom Egoyan’s words: “If you want to make a film, tape it with your home camera.” You can come up with all kinds of reasons for not making a film. I don’t want to sound like I am saying this just because I am from abroad, but the young artist that starts his day off at 11 a.m. in the morning will not be able to do much during the day. The youth here only cares about having expensive cellular phones and gets lazy. It is a matter of principles. There are many crazy people in the city, but I mean that in a good way. You really have to be crazy to spend your last pennies to make a film in this city. We simply have to let those people do their jobs, otherwise nothing will be filmed. Those people have to just open their eyes because many of them don’t even know how much potential they have. There are a lot of good kids who are hard to find. They have very narrow views and just hope for something. It seems as if Yerevan is a city of saints, but there are many dirty things going on.

– Did you realize that villagers are more kind and honest to each other while filming in Armenian villages?

– Of course. They are kinder than in the city. The person working with land can’t be anything else.

– Is there a need for individual artists in order to develop in this field?

– The “HyeFilm” studio has to work better. For example, I need a 1930s stage but “HyeFilm” doesn’t have one. They don’t give anything to anyone. They keep the stages for bigger projects. Question: what good is a film studio if it doesn’t provide the film director with the stages it needs?

– Perhaps they think that they are still in the stage of privatization.

– That may take five years. Does that mean that no film will be produced? “HyeFilm” not only doesn’t help, but also it kind of stands in the way of film directors. I am even thinking about opening my own film producing company here. I consider that a good idea because I can help many different film directors and produce 20 short films a year. The only thing that worries me is that Armenia’s “HyeFilm” studio will sit and do nothing for 20 years and just talk about the big projects. The studio is planning on paying one million dollars for a color system. What colors are you going to fix if you are not producing any films? They could have produced 15 full-length films with that money.

– Basically, going against the major film studio in the country can help the film director.

– Absolutely.

– Do short films have to do with a lack of finances?

– That is one part of it. In general, it is hard to produce full-length movies in a small country. Everyone is talking about professionalism but there are very few professionals. They just talk. Films are more often bilingual and staging is complicated. The films are far from reality.

– Perhaps people don’t know the meaning of human relations and don’t understand its value.

– America taught me how to value a person. It taught me to really value someone for who he is. America gives you the opportunity to have relations with people that you actually want to have relations with. In Armenia, you don’t have that opportunity. You have to simply adapt. In America, even the billionaire is just like me, waiting for the traffic to clear on the streets so he can move. Here, that same billionaire might just run over me. This is the difference. I am not dependent on the rich here, but the ordinary person is because only the rich person can help that person move up the ladder. Many people get up out of their seats when they see a rich person walking by, but not me. I will stay seated because that doesn’t matter to me. I am happy that I left and happy that I came back to see the country. I am going to go and come as I please. That is the only way. Man must stay strong, be dedicated to whatever he does and stay true to his people.

- People get a good education in America, right?

– To tell you the truth, after studying in America, I found out that you don’t study to be a director, you are born one. You either see yourself as a director, or no. Many don’t realize what’s happening around them. For example, I am very interested in knowing what the people sitting next to me in a café are talking about, but there are many people who don’t care about that. I think Armenians haven’t watched romance movies for a long time already. The young man today may fall in love, forgive and forget. I always argue with my friends and tell them that, for example, this café waitress may seem more than she is. She has her own dreams and expectations, just like anybody else. We must think about those kinds of people too. You have to encourage people. For example, you may talk to a taxi driver for five minutes and he may be filled with so much enthusiasm that he stops driving for a while just to come to your house and do something nice for you.

– Maybe people have just stopped listening to each other.

– If you really want to know if the city you are living in is a good or bad one, just ask a taxi driver. Taxi drivers meet thousands of different people and hear their stories every day. Nowadays, everyone wants to talk more than listen. That is why Armenian films remind us of public speeches and we don’t actually watch the film. But in reality, the moviegoer has to actually watch the film.

– Have you tried sending your films to the film studio or the Ministry of Culture to get state funding?

– I don’t even want to have anything to do with the rude people working at the film studio. I am not saying that because I am immodest, but rather because we have different principles. The film studio simply likes to intrigue. The same goes for the Ministry of Culture because the Minister is the director of the studio. That is senseless. You have to be strong and independent. You must rely on yourself. Now they tell me that they can’t give me props and lighting, tomorrow they might say that I have to pay for the technical equipment needed to shoot a scene on one of the streets of Yerevan. Well, that gets me to thinking: if I have to pay for equipment here, why can’t I just pay in America for the same scene? What can I do here? I don’t really think that Armenia will integrate into the world film industry as the film studio wants. Of course, I am one of the first that wants that to happen, but I am being realistic. Armenia is very localized. Globalization doesn’t like localization. When you watch the films of Luke Besson, you feel that the scenes were shot somewhere near the Mediterranean Sea, there are Chinese and Arab actors and for some reason, you feel like you are watching a film entirely in English. Who says that the foreigner wants to see scenes in Armenia? We Armenians need to see the scenes shot in Armenia, and the crazy people that make the films. We have to help them. Many young people with whom I have worked with in the past are now getting ready to go to Russia to make a film. They think to themselves: first, I’ll tape a wedding party so I can start making a living. This is not good in that the next time film directors in Armenia feel the need for cameras and lighting effects, they just might not find the specialists here